NOAA Fisheries NEWS – September 20, 2023 •

A government-industry survey is helping fill in the gaps on rockfish distribution and abundance in areas where standard government research gear can’t sample.

Fishing vessel, Araho, leaving port in Alaska to begin collaborative industry-government survey in Alaska. Credit: Rory Morgan

This is the third year of a successful pilot project in the Gulf of Alaska. NOAA Fisheries scientists, academic scientists at Alaska Pacific University’s FAST lab, and rockfish fishermen are working together to provide survey data in formerly inaccessible rocky areas of the Gulf. Called the Science/Industry Rockfish Research Collaboration in Alaska (SIRRCA), the team collected a variety of data on several species of rockfish. There is little data available for some of these species.

In the Gulf of Alaska, there are more than 30 species of rockfish. The focus of this study is on Pacific ocean perch, dusky rockfish, and northern rockfish.

Pacific ocean perch. Credit: NOAA Fisheries.

Based on previous NOAA Fisheries annual surveys, Pacific ocean perch numbers have increased in recent years. Dusky and northern rockfish numbers have been low. However, the habitats of all three of these species include rough, rocky areas, which are inaccessible to the NOAA Fisheries bottom trawl survey gear. This makes it difficult to get complete data on these populations. These hard-to-reach areas make up about 18 percent of the Gulf of Alaska seafloor. By working with fishermen, the science team was also able to collect needed biological information on fish condition (i.e., length, weight) for stock assessments.

Limited Data can Limit Fishing Opportunities

For dusky and northern rockfish, data from the bottom trawl survey is limited. This leads to greater uncertainty in the assessment models. When models are less precise, management measures require a much more conservative approach to prevent overfishing the fish stocks. If these stocks are healthy, this precautionary management may limit sustainable fishing opportunities.

“Sampling these rocky areas is necessary to improve our understanding of rockfish distribution and abundance and provide more accurate stock assessments so resource managers can set sustainable fishing quotas,” said Dr. Madison Hall, fisheries biologist, Alaska Fisheries Science Center who is leading the effort. “Our fishing industry partners involved in SIRRCA are fully invested in this effort to advance sustainable management for these long-lived, late maturing rockfish species. They recognize that collecting SIRRCA data and improving assessment models may ultimately increase or decrease fishing opportunities (via higher or lower fishing quotas) depending on model outcome. Better models means better management, and good management is important for sustaining both the fishery and the fish populations in the long-run. We are all on the same page about that.”

Survey Highlights

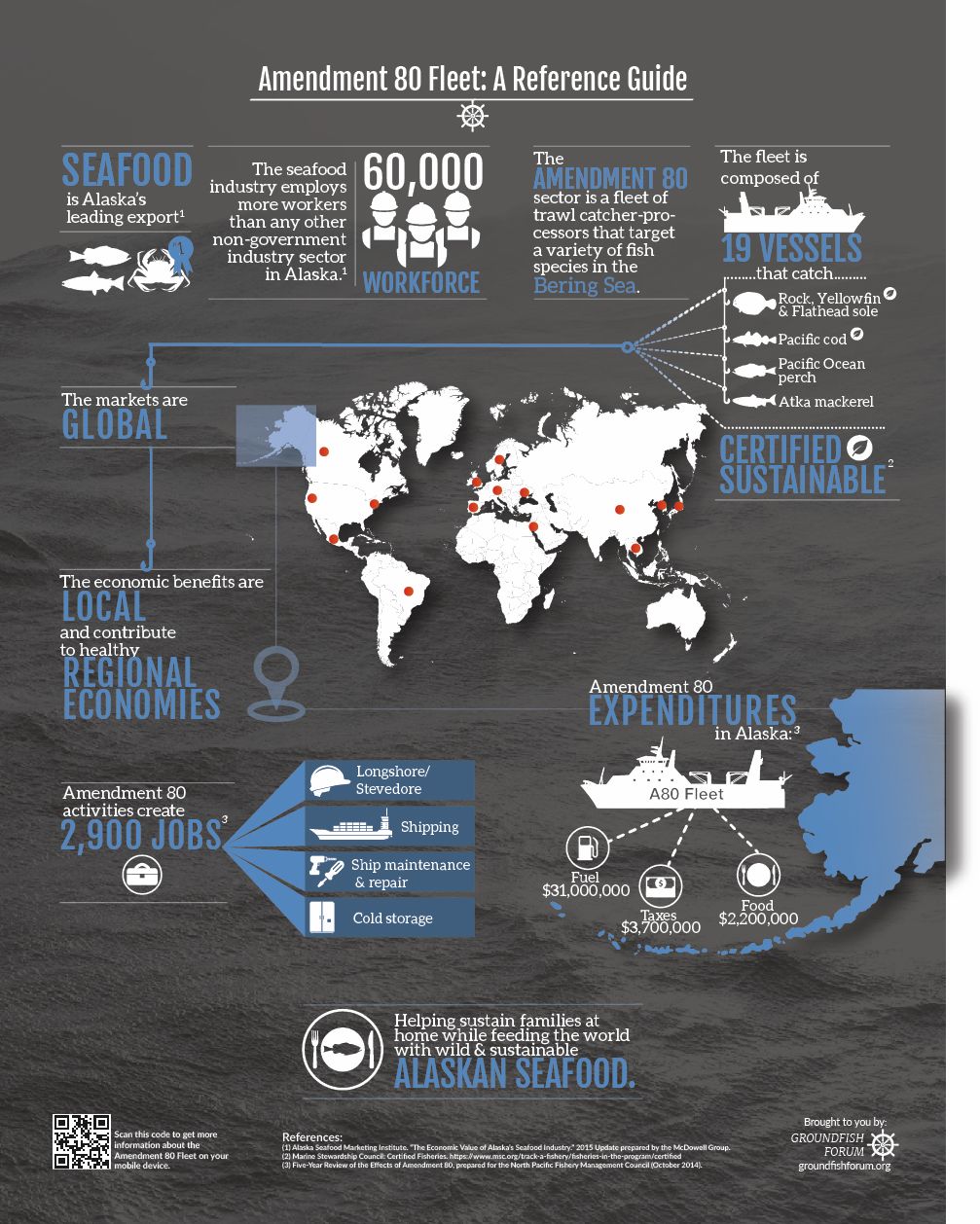

This year, the survey was conducted in June and July. The team completed 73 tows, spanning a large area in the western and central Gulf of Alaska. The research team worked with three partner vessels to conduct the cooperative survey: Amendment 80 vessels Seafisher, America’s Finest, and Araho.

“The partnership with the industry has been invaluable. Our industry partners have experience fishing in these areas. They possess the skills to safely navigate the rough terrain. This is important for unbiased data collection,” said Hall.

Commercial fishermen and their fishing cooperatives have been participating in this research for several years now. They understand this project is key to the long-term health of the rockfish populations on which they depend.

“Even if the fish we catch from the survey hauls doesn’t cover our costs for fuel and crew, conducting the survey under the scientific protocols is the right thing for industry to be doing,” said Captain Stan Morgan, F/V Araho.

Another project partner who has been involved since the project genesis is Captain Bob Hezel. Hezel is a seasoned fisherman, fishing in Alaska since the 1970s.

“The project has a lot of potential to help us unite what fishermen see on the water every day with what scientists see during their annual survey snapshots. It will fill in important gaps in the data for areas that the surveys are missing,” says Hezel. “The new information will help improve rockfish estimates and support more sustainable fisheries.”

David Rodriguez measures rockfish caught during a collaborative survey in Alaska. Photo credit: Rory Morgan

Ensuring Data Collected Can be Used in Stock Assessments

The process of developing a standardized survey took some time. First, scientists examined historical fishing industry data. They wanted to see if it could be used to calibrate rockfish catch data between industry boats and survey boats from the NOAA Fisheries bottom trawl survey. This is an important step for working industry data into blended abundance estimates.

Next, Hall and the team worked to adapt NOAA Fisheries bottom trawl survey methods to work on partnering industry vessels.

“We have to be consistent in the way we collect data. This helps ensure we can compare across areas and years. It also helps us detect trends in abundance—whether populations are going up or down,” said Hall.

Through data analysis and conversations with fishermen, scientists determined how best to assess abundance in these areas. When combined with data collected from other areas, scientists are able to get a better picture of the entire population for each of these species.

Data are being collected using different commercial fishing vessels than are contracted to conduct the annual NOAA Fisheries bottom trawl survey. So, scientists need to conduct “calibration tows.”

This year, the fishing vessels in the pilot program conducted 30 calibration tows in the same areas sampled during the annual NOAA Fisheries bottom trawl survey. They also conducted 43 experimental tows in rocky areas—areas where the standard NOAA Fisheries survey vessels can’t go. Scientists are using statistical methods to correct for any differences in catch rates between the different vessels.

“It’s important that we understand and correct for the differences in catch rates so that the data can be used to accurately estimate fish abundance in the area,” said Hall. “To do this right takes time. Vessel calibration experiments must be carefully planned and executed to produce useful and precise correction factors. This is essential to make sense of the experimental catches we see on our partnering industry vessels sampling in rocky areas.”

Scientists were able to collect important biological information from these tows. They collected:

- 51 biological samples from harlequin rockfish to be used in genetic studies

- Catch, length, and weights for Pacific ocean perch, northern rockfish and dusky rockfish

- Location information (latitude/longitude) for each of the hauls

- Acoustic information to complement biological data for estimating fish abundance

“I am quite pleased that our member companies and their vessels stepped up to fit the rockfish survey into their busy fishing seasons. They were able to cover all the locations that were selected for the survey, even if sometimes this meant steaming hours from where they normally fish. Most of all, it’s really rewarding to hear from our science partners that our captains and their crews were able to conduct the research hauls in a way that ensures the data will eventually be useful to improve rockfish stock assessments,” said John Gauvin, science projects director for the Alaska Seafood Cooperative. “We’re hopeful that this project will demonstrate the value of industry-science partnerships to augment this and other fisheries data collection efforts.”

What’s next for the rockfish project?

The team plans to hold a workshop in the fall to review how the survey went and develop a plan for the future of the project. There also is a substantial amount of data to analyze from this year’s hauls in both calibration and experimental tows. With 3 years of data, the next phase of the project will be working to integrate the data into the stock assessments.

“We need to collect enough data to make real improvements to the population estimates, but also we need to make sure our industry partners are not overburdened by the sampling methods. We know that going to these additional areas uses extra fuel and takes time away from commercial fishing and that the survey catches are too small to fully compensate for this. We have to find a level of sampling that works both for the survey and our industry partners,” said Hall.

Beyond that, the team hopes to expand the cooperative rockfish survey efforts to include other rockfish species/groups (e.g., harlequin) and regions (i.e., the Aleutians).

Special thanks to:

- John Gauvin, the Alaska Seafood Cooperative

- The Groundfish Forum

- The Alaska Groundfish Databank

- AIS Observers Inc.(Luke Syzmanski, Rory Morgan, David Rodriguez)

- Dr. Brad Harris from Alaska Pacific University

- Fishermen’s Finest (Captain Bob Hezel, Captain Erin Moore, Annika Saltman, the crew of the America’s Finest)

- Ocean Peace (Captain Pat Haley, Todd Loomis, the crew of the Seafisher)

- The O’Hara Corporation (Captain Stan Morgan, Jason Anderson, Frank Fogg, Mary Beth Tooley, the crew of the Araho)

National Fisherman – Guest Author Ray Hilborn – July 21, 2022 •

A Kodiak-based groundfish trawler. Alaska Whitefish Trawlers Association photo.

With the launch of several recent advocacy campaigns, bottom trawling is squarely in the crosshairs of some environmental groups and media outlets that regurgitate their press releases.

There is no question that bottom trawling has environmental impacts, as all food production does, but there is misinformation floating around about the true impact of bottom trawling, especially in comparison to other types of fishing and food production. With campaigns like #BanBottomTrawling growing, I want to look at what the science says about the sustainability of bottom trawling.

Sustainability of target species

Many trawl fisheries are certified by the Marine Stewardship Council and recommended by Seafood Watch. Groundfish populations around the world are largely caught by trawls and are, on average, increasing. Certainly, some stocks like New England cod are in poor shape, but it has nothing to do with the method used to catch them.

Impact of trawling on benthic ecosystems

A defining characteristic of bottom trawling is that it uses nets that are dragged along the seafloor. These nets certainly impact the plants and animals that grow on the bottom, but the overall impact of trawling depends on the sensitivity of the individual species, the kind of fishing gear, the underlying geology of the seafloor, and the frequency of trawls.

Some benthic species such as soft corals and sponges are quite sensitive to bottom trawling because they stick well above the bottom, and they are very slow growing. A few passes of the net may eliminate them completely, and it may be decades before they return.

However, a major paper published last year found that across all regions studied, less than 10 percent of trawled area had lost more than 20 percent of its benthic fauna. The vast majority of trawled areas had lost less than 10 percent of the benthic fauna, and the largest U.S. trawl fisheries in Alaska, only a few percent.

This is a huge win for effective fishery management, but is also explained by the fact that most bottom trawling occurs on sand or mud (not reefs), where the habitat is quick to regenerate and the species that live there are evolved to be resilient to disturbance.

Good management can reduce impacts on benthic ecosystems by closing areas with high density of corals and sponges to bottom trawls, by modifying the fishing nets so that the heavier parts do not touch the bottom, and even by not letting the nets touch the bottom. Many trawlers now use nets that barely touch the bottom.

Bycatch and discards

Almost all fishing gear catches non-target species. If these are not of commercial value they are usually discarded at sea, a waste of fishermen’s time and energy, and a pointless loss of life. Bottom trawling discards and bycatch rates vary greatly, with shrimp fisheries discarding the most, but well-managed bottom trawling can almost totally avoid discards. The bottom trawl fishery in the Bering Sea discards less than 8 percent of its catch.

Bycatch has been reduced or eliminated by modifying net design and ways of fishing, and by sharing information within fishing fleets. In Asia everything caught is retained, and the non-marketable species are used for surimi or aquaculture feed.

Several groups around the world are working on using cameras at the mouth of the net to identify the species and size of fish entering the net, and opening panels that eject the unwanted fish. Discarding is being reduced and nearly eliminated in some fisheries that have made it a priority.

Carbon footprint

The major source of carbon footprint from fishing is from fuel use. One major review showed that bottom trawling was the second highest user of fuel, exceeded only by pot and trap fishing. But there are enormous differences in fuel efficiency depending on the kind of trawl, the age of the vessel, and the abundance of the fished species.

Nearly all trawled fisheries have better carbon footprints than beef. Some have a carbon footprint below chicken and pork and comparable to corn.

Bottom trawling’s carbon impact was all over the news last year when a paper published in 2021 argued that by stirring bottom sediments, bottom trawling released more carbon than air travel. The paper is deeply flawed and has been heavily criticized: other estimates are 100 times lower than the headline-grabbing paper.

The carbon footprint of bottom trawling will continue to decrease as inefficient engine systems are replaced with modern diesel engines and eventually, by hydrogen or electric vessels. Improvements in net and boat design are also improving efficiency. Most importantly, healthy fisheries require less fuel to harvest, so improving stock status is paramount.

Conclusion

Banning bottom trawling is not the right approach to global sustainability. Even the worst impact of bottom trawling on benthic ecosystems is less damaging than agriculture, which completely destroys forests and grasslands to produce food.

Catching fish in the ocean uses no pesticides or fertilizer, no freshwater, no antibiotics, and no land. Bottom trawling produces about one-half as much food as global beef production. If it is banned, where will we make up that food?

The way to sustain food production and minimize the environmental impacts is not to ban trawling, but to manage it by providing incentives to the fishing fleets to minimize bycatch, reduce fuel use, minimize benthic impacts, and protect sensitive habitats.

Ray Hilborn is a professor in School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences at the University of Washington.

Seattle Times – By Hal Bernton, Seattle Times staff reporter – December 13, 2021 •

A federal fishery council vote Monday could set the stage for future cuts of up to 35% in the incidental halibut take of a largely Washington-based trawl fleet that targets yellowfin sole and other flatfish.

The high-stakes 8-3 vote in an online meeting by the North Pacific Fishery Management Council is likely to result in a big financial hit to this fleet of 19 bottom-trawl vessels. The fleet’s annual $350 million in revenue could be reduced by up to $110 million if halibut stocks are found in surveys to be in very low abundance, according to industry officials.

The council action followed several days of often emotional testimony in an ongoing fisheries battle over the scope of the trawlers’ catch of a revered flatfish — found off the west coast, British Columbia and Alaska — that surveys indicate have largely been in decline during the past 15 years.

In 2019, the bottom-trawl fleet’s incidental take, or bycatch, of halibut tallied nearly 3.1 million pounds as vessels used huge nets to scoop up 635.4 million pounds of yellowfin sole and other flatfish. For the trawl fleet, these halibut are a prohibited species and must be jettisoned overboard.

Some of those trawl fleet’s halibut discards survive. But in 2019, 1.4 million pounds’ worth of halibut did not survive the nets. And over the years, the scope of these discards has angered tribal, sport and commercial fishers who land these fish with hook-and-line gear.

The bottom-trawl fleet’s current cap is a fixed amount that does not vary from year to year. If the fleet reaches that cap, the vessels must stop fishing. The council lowered that cap by 25% in 2015 and the fleet has stayed under the limit. But that action did not quell the movement to further lower trawl discards.

Opposition has flared among halibut fishers in the Northwest and Canada, and has been very intense in Alaska coastal communities.

Halibut fishers have seen their own quotas shrink and have demanded that the trawl fleet’s halibut take also come down. In many Alaska costal communities, halibut is often both an important local food source and also a significant source of revenue when sold for processing and delivery to seafood markets in the United States and elsewhere.

“Halibut bycatch must be reduced immediately,” said Simeon Swetzoff Jr., a former mayor of St. Paul in Alaska’s Pribilof Island and a Bering Sea halibut fisher who has long lobbied to limit the trawl discards.

The nets on this vessel are pulled along the bottom to target flatfish in areas of the Bering Sea where halibut also are found. The halibut brought on board must be thrown back. (Courtesy of Groundfish Forum)

In the Bering Sea region, the amount of halibut last year thrown overboard by the trawl fleet exceeded the amount caught by hook-and-line fishers. In his council testimony, Swetzoff said that the “bolts (on the trawl fleet) need to be tightened. … We have tried everything there is to possibly do.”

Representatives of the bottom-trawl industry say that over the past decade they have made major strides in reducing their bycatch. Those efforts include cooperative efforts to avoid halibut hot spots and deck-sorting to more quickly return halibut to the sea. They are doubtful they can make further reductions to comply with the council action, which could reduce their discard quotas by up to 35% in years when surveys indicate halibut are in very low abundance.

“We are shocked that the council made this decision, and come to this conclusion,” said Chris Woodley, executive director of the Groundfish Forum, which represents the bottom-trawlers known as the “Amendment 80” fleet.

Woodley said that the fleet is a huge provider of frozen fish protein. Much of that fish is exported to Asia but it includes fillets marketed as flounder skinless fillets that can be found in U.S. supermarkets. He said the action will hit hard not only boat owners but also some 2,200 crew who catch and process this fish.

Industry officials say that they would likely have to tie up their boats long before their total flatfish quotas are caught. That could result in this fleet providing up to 200 million less fish meals, according to statement released by the Groundfish Forum.

Woodley noted that an analysis by council staff found that the overall “net benefits to the nation” from this action would be negative. He said no decision has been made by his group about whether to eventually pursue legal action over the council’s action.

The council, with 11 voting members, was formed by congressional legislation and is empowered to come up with harvest rules that are then put into final form by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries.

The council is composed of fishing industry as well state and federal officials, with Alaskans controlling the biggest share of the voting seats on the council.

Alaska council members who voted in favor of the message were joined by one Washington state council member and a federal representative.

Their leadership to push through was praised by Jeff Kaufman, a vice president of the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association who said it will “better manage the resource.”

Those opposed included Bill Tweit, a Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife official who questioned whether the surveys that would be used to determine halibut abundance were accurate enough to put this new rule into action.

“No changes to this framework would make this defensible and actually functional,” Tweit said during the council meeting. In his remarks, Tweit also said that the current conservation management is capable of maintaining adequate stocks of spawning halibut.

Hal Bernton: 206-464-2581 or hbernton@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @hbernton.