Seattle Times – By Hal Bernton, Seattle Times staff reporter – December 13, 2021 •

A federal fishery council vote Monday could set the stage for future cuts of up to 35% in the incidental halibut take of a largely Washington-based trawl fleet that targets yellowfin sole and other flatfish.

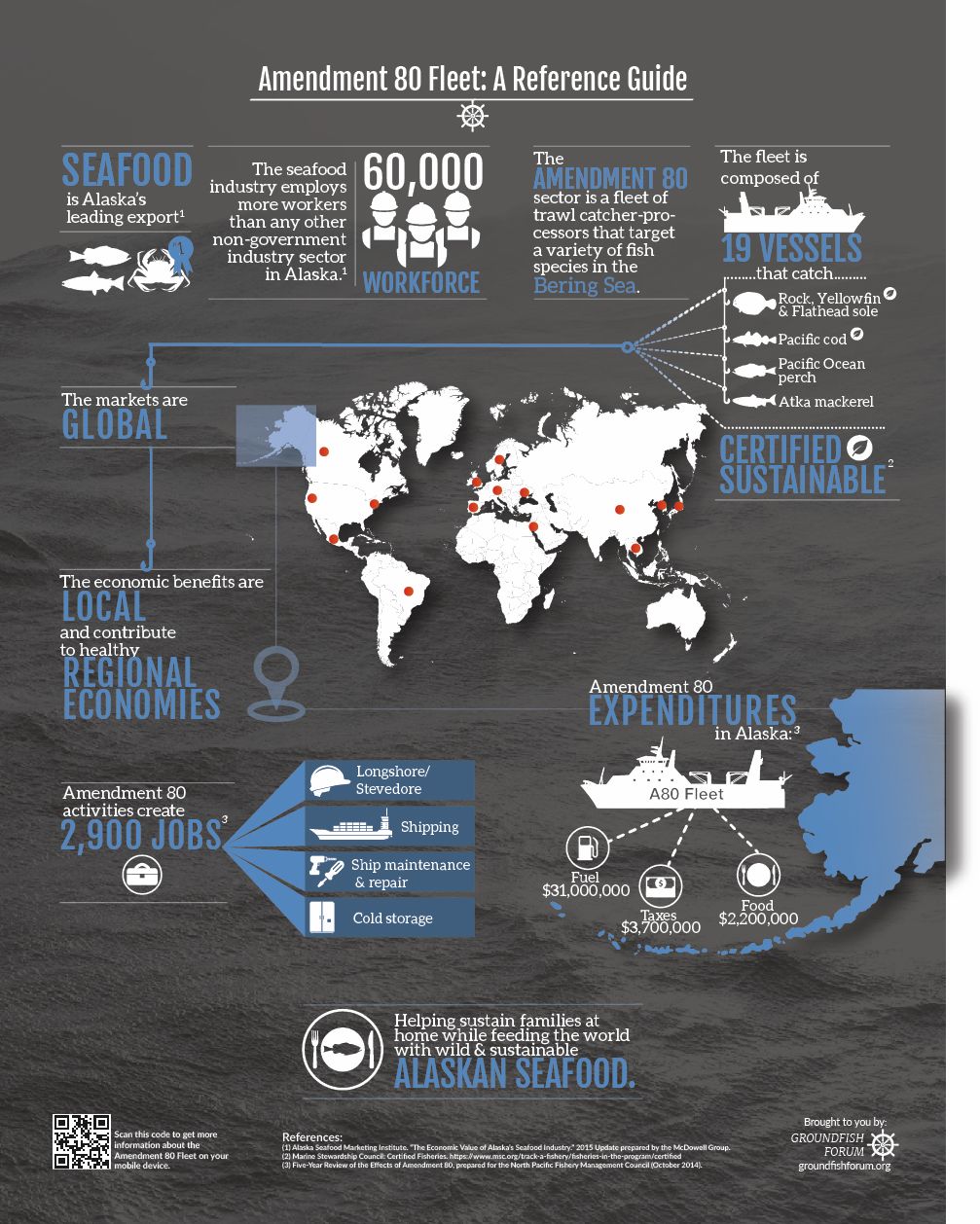

The high-stakes 8-3 vote in an online meeting by the North Pacific Fishery Management Council is likely to result in a big financial hit to this fleet of 19 bottom-trawl vessels. The fleet’s annual $350 million in revenue could be reduced by up to $110 million if halibut stocks are found in surveys to be in very low abundance, according to industry officials.

The council action followed several days of often emotional testimony in an ongoing fisheries battle over the scope of the trawlers’ catch of a revered flatfish — found off the west coast, British Columbia and Alaska — that surveys indicate have largely been in decline during the past 15 years.

In 2019, the bottom-trawl fleet’s incidental take, or bycatch, of halibut tallied nearly 3.1 million pounds as vessels used huge nets to scoop up 635.4 million pounds of yellowfin sole and other flatfish. For the trawl fleet, these halibut are a prohibited species and must be jettisoned overboard.

Some of those trawl fleet’s halibut discards survive. But in 2019, 1.4 million pounds’ worth of halibut did not survive the nets. And over the years, the scope of these discards has angered tribal, sport and commercial fishers who land these fish with hook-and-line gear.

The bottom-trawl fleet’s current cap is a fixed amount that does not vary from year to year. If the fleet reaches that cap, the vessels must stop fishing. The council lowered that cap by 25% in 2015 and the fleet has stayed under the limit. But that action did not quell the movement to further lower trawl discards.

Opposition has flared among halibut fishers in the Northwest and Canada, and has been very intense in Alaska coastal communities.

Halibut fishers have seen their own quotas shrink and have demanded that the trawl fleet’s halibut take also come down. In many Alaska costal communities, halibut is often both an important local food source and also a significant source of revenue when sold for processing and delivery to seafood markets in the United States and elsewhere.

“Halibut bycatch must be reduced immediately,” said Simeon Swetzoff Jr., a former mayor of St. Paul in Alaska’s Pribilof Island and a Bering Sea halibut fisher who has long lobbied to limit the trawl discards.

The nets on this vessel are pulled along the bottom to target flatfish in areas of the Bering Sea where halibut also are found. The halibut brought on board must be thrown back. (Courtesy of Groundfish Forum)

In the Bering Sea region, the amount of halibut last year thrown overboard by the trawl fleet exceeded the amount caught by hook-and-line fishers. In his council testimony, Swetzoff said that the “bolts (on the trawl fleet) need to be tightened. … We have tried everything there is to possibly do.”

Representatives of the bottom-trawl industry say that over the past decade they have made major strides in reducing their bycatch. Those efforts include cooperative efforts to avoid halibut hot spots and deck-sorting to more quickly return halibut to the sea. They are doubtful they can make further reductions to comply with the council action, which could reduce their discard quotas by up to 35% in years when surveys indicate halibut are in very low abundance.

“We are shocked that the council made this decision, and come to this conclusion,” said Chris Woodley, executive director of the Groundfish Forum, which represents the bottom-trawlers known as the “Amendment 80” fleet.

Woodley said that the fleet is a huge provider of frozen fish protein. Much of that fish is exported to Asia but it includes fillets marketed as flounder skinless fillets that can be found in U.S. supermarkets. He said the action will hit hard not only boat owners but also some 2,200 crew who catch and process this fish.

Industry officials say that they would likely have to tie up their boats long before their total flatfish quotas are caught. That could result in this fleet providing up to 200 million less fish meals, according to statement released by the Groundfish Forum.

Woodley noted that an analysis by council staff found that the overall “net benefits to the nation” from this action would be negative. He said no decision has been made by his group about whether to eventually pursue legal action over the council’s action.

The council, with 11 voting members, was formed by congressional legislation and is empowered to come up with harvest rules that are then put into final form by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries.

The council is composed of fishing industry as well state and federal officials, with Alaskans controlling the biggest share of the voting seats on the council.

Alaska council members who voted in favor of the message were joined by one Washington state council member and a federal representative.

Their leadership to push through was praised by Jeff Kaufman, a vice president of the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association who said it will “better manage the resource.”

Those opposed included Bill Tweit, a Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife official who questioned whether the surveys that would be used to determine halibut abundance were accurate enough to put this new rule into action.

“No changes to this framework would make this defensible and actually functional,” Tweit said during the council meeting. In his remarks, Tweit also said that the current conservation management is capable of maintaining adequate stocks of spawning halibut.

Hal Bernton: 206-464-2581 or hbernton@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @hbernton.

Anchorage Daily News Opinions – By Bob Hezel and TJ Durnan – December 10, 2021 •

The factory trawler American Triumph docks in Seward on July 22, 2020. (Loren Holmes / ADN)

We are two captains with a combined experience of more than 70 years in Alaska’s groundfish trawl fisheries.

In that time, we’ve been a part of a trawl fishery that has evolved and innovated heavily to meet several regulatory challenges. This is thanks to a collective commitment of the 2,200 fishermen and women who participate in our fishery. Our families are fishing families, too – as important as any other. We believe we are true stewards of the North Pacific resources. But cuts to our halibut bycatch caps under consideration by the North Pacific Fishery Management Council at its upcoming December meeting threaten our fishery and our way of life.

Our fleet has achieved a 49% reduction in halibut bycatch mortality since Amendment 80 rationalization in 2007. Halibut now represents 0.4% of our catch, which is among Alaska’s lowest bycatch rates, and far lower than Canada’s West Coast fisheries, which are often held up as an example of low bycatch rates. But it has not been easy to get here.

Over the past 10 years, we have designed and developed numerous technologies to lower bycatch in our nets, including halibut excluders and elevated sweeps to reduce bottom contact. These technologies have been implemented with great cost in time, material, and lost productivity of our vessels — not to mention all the frozen hours out on deck for our crews who have willingly helped us to create and refine these devices. While some of these gear modifications showed promise for reducing halibut catches initially, now that halibut are mostly about the same size as our target fish there is no sensible reason to expect that anything more than very marginal gains will come from additional innovation in the field of net and excluder design. This is the industry consensus of captains, net and excluder engineers, and technicians.

We have also worked hard to develop operational methods of reducing halibut bycatch. As a fleet, we’ve developed deck sorting procedures which greatly reduce halibut mortality, returning far more of these fish live to the sea while maintaining accurate observer accounting. We started this work in 2009 with two vessels, expanding and refining the program over many years. This program has been a remarkable success, and it has recently been accepted into regulation by the National Marine Fisheries Service. However, the consensus of captains, scientists and crews is that all the gains from these methods have already been achieved.

While we are always looking for new innovations, we know of no new piece of gear that gets us to a place where we can take another cut. This means that the halibut cuts under consideration for our fleet will force a dramatic contraction in the target harvest. This will have devastating impacts on our fishery and the people who work so hard in it. The council’s own review acknowledges that there are no new tools for us and indicates that an average Amendment 80 crew member stands to lose $24,000 to $48,000 in income annually from the cuts the council is considering. The benefit to a halibut crew member for cuts to our fishery? $500 to $1,000 a person.

The people in western Alaska who provide goods and services also stand to lose a large source of revenue due to the harvest contraction. Unlike many other fisheries, our sector has traditionally operated year-round, and we bring much needed economic opportunity to coastal communities. This year-long stability and revenue is in danger.

Too often, this issue has been framed as a battle between small operators vs. large corporations. We are not large corporations. We are people and this is our job. We are 2,200 crew members who work tirelessly to earn an honest, decent living and support our families. Our crews come from all walks of life, and we have been able to provide a standard of living that many may not have been able to achieve elsewhere.

The council’s proposed cuts might be understandable if there were a proportional gain to another fishery or a conservation benefit, but the council’s own analysis states that cutting our halibut bycatch further will not improve halibut stocks or yield conservation benefits. According to the science, our halibut bycatch is not the cause of declines in the halibut fishery.

So, when the council meets on halibut bycatch in early December, they need to look to their own science and not make cuts that threaten our fishery and provide no benefit to halibut fishermen. Our families are depending on it.

Bob Hezel is captain of C/P America’s Finest and TJ Durnan is captain of C/P Alaska Spirit, two factory trawlers for Fishermen’s Finest and O’Hara Corp., based in the Seattle area. Both boats fish for wild Alaska sole and flounder, Pacific cod, Pacific ocean perch, and Atka mackerel in Alaska’s Bering Sea.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by the Anchorage Daily News, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary(at)adn.com. Send submissions shorter than 200 words to letters@adn.com or click here to submit via any web browser. Read our full guidelines for letters and commentaries here.

Alaska Journal of Commerce – By Elizabeth Earl – November 24, 2021 •

Keith Pearson, left, pushes a halibut as the Auction Block Company crew offloads the fish from a boat, Aug. 9, 2016. The fish are sorted by size, iced and boxed for moving. (Anne Raup/ADN archive)

After years of deliberations, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council is inching toward a decision on whether to tie halibut bycatch limits in the Bering Sea to abundance indices.

The action, known formally as Bering Sea-Aleutian Islands halibut abundance-based management, or ABM, is intended to reduce bycatch of halibut in the Bering Sea by the Amendment 80 trawl fleet when the fish stocks are lower. The Amendment 80 fleet is a group of catcher-processor vessels that are allocated a portion of groundfish harvest. Each year, the fleet is bound to a hard limit on how many halibut they can take as bycatch, known as the prohibited species catch, or PSC limit.

That limit is fixed, however, while halibut stocks and the allowable catch for the directed fleet vary. Over the last six years, the council has been considering whether to instead adjust the PSC limit to fluctuate with halibut abundance indexes based on two surveys, effectively pushing more of the halibut available for harvest to the directed fishery fleet. Depending on which of four alternatives the council chooses — from no action to varying changes —the effects could range from a 45% cut to a 15% increase, depending on abundance.

Chris Woodley, executive director of the Groundfish Forum, a trade association representing members of the Amendment 80 fleet, said the draft environmental impact statement provided to the council points out that a shift to ABM would overall be detrimental economically.

“There are a number of things the Groundfish Forum is concerned about — the primary one being that the draft EIS is very clear that there is going to be little to no benefits to the halibut stocks or to conservation in general and that the net (economic) benefit to the nation is expected to be negative,” he said. “That’s very up front and very clear.”

The issue has been controversial from the beginning, in part because of the cost to the trawl fleet. The National Marine Fisheries Service estimates that cost to the Amendment 80 fleet would be between $68 million and $138 million, depending on fishing variables and the alternative implemented. By contrast, the draft EIS estimates that the economic benefit to the directed halibut fleet would be between $1.1 million and $2.2 million. There are about 835 crew positions in the Amendment 80 fleet, compared to about 400 in the directed fishery for halibut in the region. Because the loss is so large and the number of people relatively small, the reduced revenue would pencil out to about a $30,000 loss per crew position in the Amendment 80 fleet under one alternative.

“There’s virtually zero upside to the directed fishery and a huge amount of downside to the Amendment 80 fishermen,” Woodley said.

Though the review concludes that the net benefit of implementing abundance-based management would be negative economically, both the social and economic impacts are considered. Diana Stram, a senior scientist with the NPFMC who worked on the document, said the statement about the net benefits is largely an economic one.

The council is bound to consider the 10 national standards under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, which include standards like conservation, minimizing bycatch to the extent practical and minimizing costs. Stram said the council must balance its decision across those standards.

“Certain actions are going to be more related to one of the national standards than others,” she said. “What we do as analysts in the document is we try to provide some narrative to help the decision-makers understand how this plays into their actions, but the onus is on the council if one alternative is balancing one standard higher than another.”

None of the four alternatives have a significantly different impact on the spawning stock biomass for halibut in the Bering Sea, according to the draft EIS. That’s because the International Pacific Halibut Commission manages the halibut stocks as well and sets the catch limits based on its survey for sustainable harvest levels, Stram said. Whatever the council decides to do would only affect the amount of fish available for harvest, not the spawning stock.

Some fishermen in the Bering Sea region are pushing for the council to enact the motion both out of economic and sustainability concerns. The directed halibut fleet in the Bering Sea is one of the economic mainstays for coastal communities in Western Alaska. Halibut is also a critically important subsistence resource in many of the communities of the Aleutian Islands and Bering Sea, particularly as other stocks like crab decline.

St. Paul Island is one of those communities. The island, with a population of about 480 people, depends on subsistence foods and commercial fishing. Halibut is a staple there, and the community has a vested interest in the long-term sustainability of the stock, said Lauren Divine, the director of the ecosystem conservation office for the Aleut Community of St. Paul.

None of the alternatives are enough to do what the community feels is necessary, but they want to see something happen, she said.

A number of other halibut-dependent coastal communities have already stopped fishing for halibut, in part because of the decline connected with the static bycatch cap, Divine said. The community of St. Paul is home to a Community Development Quota group, the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association, and people on the island do depend on fishing jobs, but it’s not just about the economics for community, Divine said.

“From an Indigenous community perspective, it’s not just about money,” she said. “It’s a way of life people don’t want to give up.”

Heather McCarty, a fisheries analyst who works with the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association, said the group is advocating for Alternative 4, but feels for a number of reasons that the draft EIS doesn’t provide enough information for the council to make a decision. For one, she said Alternative 4 is the only option that meets the council’s purpose and needs statement for the project. For another, the draft EIS focuses on the perspectives of the CDQ groups, which may not always be the same as the perspectives of the communities.

The group supports the action because it would help spread out the burden of conservation to the trawl fleet, she said. Because the bycatch cap is static, in some years, the trawl fleet might be able to take nearly all the halibut available for harvest.

“The directed fishermen bear the entire burden of conservation,” she said.

Divine said the Aleut Community of St. Paul also finds Alternative 4 preferable.

“Alternative 4 isn’t enough, but it is a good start as we move into abundance-based management away from static caps,” Divine said. “But I think this is going to be an ongoing (issue).”

Stakeholders on both sides of the discussion agree that the EIS has some information holes in it that need to be addressed before the council uses it to take action, including on topics such as the effects of climate change on fish populations.

The council is expected to take action on BSAI halibut abundance-based management at its upcoming meeting beginning Dec. 8.

Both McCarty and Divine said the communities aren’t advocating for the trawlers to be completely closed, but for there to be a more equitable division.

National Standard 9 of the MSA requires the council to reduce bycatch to the extent practicable. The Amendment 80 fleet has taken multiple steps to reduce halibut bycatch as more attention has turned to the issue. Since 2007, the fleet’s bycatch is down by 49%, the vessels have reduced their bottom contact by an estimate 90%, and are communicating about areas with higher halibut bycatch to avoid fishing there. They are also using excluders, deck sorting, avoiding night fishing and using small tows, among other efforts. In the past few years, the fleet has encountered high numbers of halibut on the grounds, such as in 2019, when record-breaking warm waters affected fisheries all over Alaska.

Woodley said one of the fleet’s concerns is that the 2019 conditions will become a new normal, so the fleet wants more flexibility within bycatch regulations to adapt.

“We are committed to continued halibut bycatch reduction, but with halibut bycatch already so low and with all current tools fully utilized, future efforts will likely result in only small incremental improvements.”

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabethearl@gmail.com.